Today, many are celebrating the Constitution Act 1867, otherwise known as confederation. For most, this is a time for national pride and honouring all that is ‘Canadian’. For Indigenous People like me on a journey of decolonizing, July 1st is a day off work and time to reflect on the idea of nationhood and our personal relationship to Canada. I think about this a lot – on what it means to be a Canadian citizen. On what about this country I am actually proud of. On the investment I make daily to speak truthfully about the past that has brought us all here.

Telling the story of our shared history to Canadians and to the world is an uphill battle. What we are taught through our education system and the narrative perpetuated in society is a colonial one. It’s based on the idea of terra nullius, or empty land, that was ‘discovered’ by Europeans and put to good use. I remember in grade school learning about Cartier and Cabot that arrived on the eastern shores to settle, create colonies, and eventually move west. I learned that the only role of the Indigenous Peoples who were here before them was to help them learn to survive in the harsh climate and furnish them with beaver pelts. Sound familiar?

As an adult, I have come to know that I, like others, was fed a lie. Canada was not founded or created, it was colonized. The Peoples who had been here for tens of thousands of years prior to European contact were decimated. My ancestors who survived the centuries of genocide did so out of inner strength and resilience based in cultural teachings. It’s because of them that I am here and I will not allow their struggles to go unrecognized or unheard.

Over the past 200+ years, the perspectives and knowledge from Indigenous Peoples in this country have been minimized, marginalized, and bastardized to ensure that the dominant narrative of colonial settlerhood reigns. But this is starting to shift. More Indigenous People are standing up for truth and refusing to be silenced. More investments are being made in the documentation and amplification of Indigenous voices. Yet efforts are still made to make sure the balance of power and truth remains skewed in favor of the colonizers.

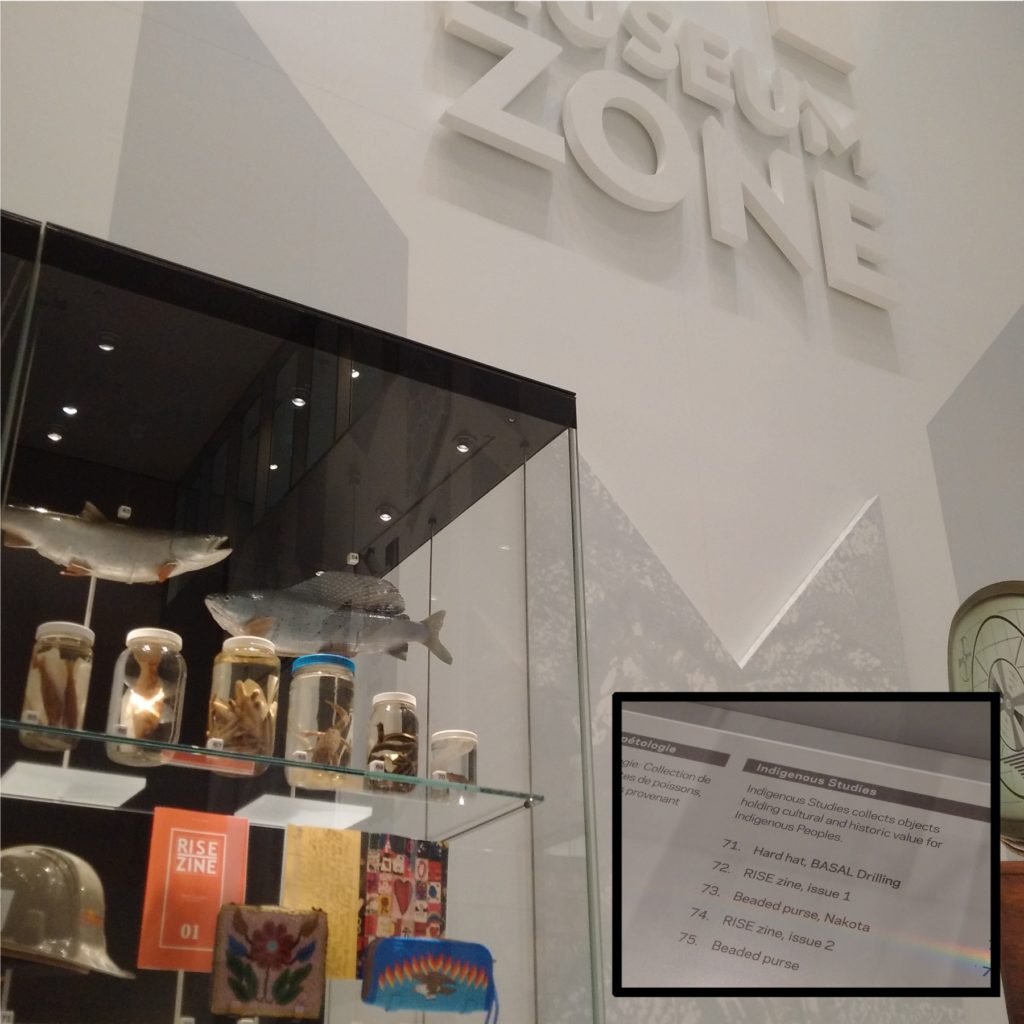

Which brings me to the publicly-funded Royal Alberta Museum (RAM) which re-opened last year in a new building in downtown Edmonton. In this time of reconciliation, I had hopes that the RAM would use it’s new facility to create exhibits that approached the story of Alberta in a more balanced way. I hoped the museum would acknowledge its own founding story based on stolen artifacts and pioneering settlement. Ultimately, I hoped that Indigenous stories of this place would inform the story we tell about who we are as people who make our homes here now. My hopes were all but shattered on my first visit to the RAM last fall shortly after it opened.

It took me a while to process how much the RAM had truly missed the mark. It started with a feeling in my gut of disgust and anger that I couldn’t verbalized at the time. As I walked through the galleries, I was overwhelmed with how much everything was the same as before, perhaps a bit shinier, but the same. Yes, there were some noticeable differences – the presentation of the manitou asiniy, the smattering of Indigenous displays throughout the museum instead of clumping everything together, and the presence of Indigenous languages. That visit left me wondering why they chose to take only a few small steps down this path of truth rather than make leaps and bounds. Why didn’t they do better? Was it because of resources? Time? Willingness? Or all of the above?

That night I remember running into a few people I knew at the RAM who had also been invited for this private, invitation only event. The settler acquaintances were overwhelmingly in awe of the spectacle that was the new museum. The Indigenous friends were politely pensive. As the weeks and months rolled on and more people had a chance to see the museum, I had the opportunity to talk with others about their impressions of the new RAM. Through these conversations, I was able to focus my own thoughts and reactions to what I had experienced.

A while back, I was invited as a guest to the Canadian Art Gallery Educators symposium held in Edmonton over three days in May. On the final day of the gathering for gallery educators from across Canada, I was on a panel of Indigenous people sharing personal insights. As their guest, I was also able to join in on the other days for tours, workshops, presentations, and networking. When I reviewed the schedule and saw the guided tour of the new RAM, I decided it was time to go back and check in on the feelings I had from my first visit more than six months before. This visit would also allow me to snap a few photos for this blog post that had been festering inside for months.

So what exactly ticks me off about the RAM? I can summarize my feelings in these few points:

1 – Indigenous Peoples had no influential voice in the museum’s creation or renewal.

In Fall 2017, about a year before the new museum opened to the public, I was approached to participate in the Indigenous Advisory Panel. With this panel being formed so close to public opening, it was evident that they were not actually looking for advice that could be implemented but rather, approval of the decisions already made. At this point, the content and design for the main galleries had already been decided, the text panels were written and final construction was nearing completion. In actuality, the RAM wanted rubber-stamping Indigenous People to be champions for them to parade around and say “look at everyone who helped us” providing validity to their colonial practices. No thanks. Like the very premise of settler colonialism, museums are based on the idea of a self-appointed superior culture (ie. the colonizer) deciding they know best and making decisions without including those who are impacted the most. The dominant culture is continuing to steer the narrative and decide how the story of our past and present is told.

2 – The truth about how artifacts in the collection were acquired is going untold.

When the first provincial museum opened in 1967 as a centennial project, museology was in it’s pillaging prime. Their goal was to ‘acquire’ items for their collection, perhaps by any means necessary to meet the deadline of opening day. This included using public funds to buy stolen cultural artifacts via pricey auction houses and sending out contracted staff paid with finder’s fees. Both practices removed the museum and the provincial government from directly getting their hands dirty but doesn’t change the story of how these items came to be in the RAM’s possession. For the Indigenous items in their collection, these range from tools from archaeological sites and centuries old beadwork to sacred bundles and items of cultural use taken when ceremonies were outlawed. In order for reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples to be seen as plausible, it must be grounded in truth. The museum needs to tell the truth about who they are and how they came to be in order to have credibility with me and with others. When they are willing to tell the truth about their collection, the next step must be repatriation and redress for the loss. PS: don’t let their mention of this on their website fool you. Their definition of repatriation is like long term loan and covers only Blackfoot items at the moment.

3 – Indigenous content is presented through a lens of white fragility.

For me, this is the worst part. It’s like the museum made a decision to incorporate Indigenous content throughout the museum, rather than repeating the old Syncrude Hall of Aboriginal Culture, but wanted to make sure it wasn’t upsetting in any way to the their paying settler customers. There are some specific examples of this in the Human History Hall that caused the most visceral reactions from me.

The first is the placement and language of the residential schools story. The display sits in a closed off, circular space in the middle of the floor of the gallery, surrounded by unrelated content. I have spoken with so many people who visited the museum and didn’t even know there was a residential school exhibit or they had seen that particular display but didn’t know it was telling the story of residential schools. Unless you are looking for it specifically or are connected to the story in some way, it’s easy to miss it all together. Through the work of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, this truth is now available to Canadians. To honour the courage of survivors, we need to tell it in an honest, heart wrenching way.

The second example is actually not Indigenous content at all, it’s the presence of the Sunwapta Broadcasting totem pole. Yes, this is a part of Alberta’s past and for some brings back fond memories of yesteryear, especially for settlers who grew up in Edmonton and Northern Alberta. But the act of reconciliation lies in the way we tell this story. The name of this private media company and it’s choice to be branded with totem poles is First Nations cultural appropriation. Sunwapta is from a Stoney Nakoda word and totem poles are cultural practices of many Pacific Northwest First Nations, neither of which are from the traditional territory on which Edmonton was founded. I think that sharing these few sentences with museum visitors would make them feel uncomfortable and put a negative slant on the way they remember the past. This discomfort would not likely to create a repeat visit, and may be a reason why the RAM has shied away from truthtelling.

4 – Indigenous Peoples are still othered and not presented as foundational.

At the root of all of it, this is the problem. The RAM and us as Canadian citizens don’t recognize that the reason we are here in Treaty Six territory is because of Indigenous Peoples. The way in which information about Alberta is presented at the RAM does not consider this fact and puts the focus on the human inhabitants of the last 200 years, rather than the first 20,000+ years. The relative focus of each era implicitly tells visitors what is important. Indigenous voices, perspectives, and opinions have been purposefully excluded at the expense of telling more settler stories, the feel-good memories that perpetuate the pioneering narrative of taming the wild west. Museums like the RAM hold positions of power in the telling of these stories and underlining what is important for each of us to learn about. If these decisions continue to be made by white scholars who have a vested interest in maintaining power, how can we ever know the full truth? When will people from the cultures represented in the museum’s collection be put in charge of how their items are displayed or allowed to decide if that should even happen at all?

One act of reconciliation the RAM announced early on was free admission to the museum for Indigenous Peoples. Not charging me admission to see the items you stole from my ancestors is the VERY LEAST thing you could do. The First Peoples of this place were robbed of culture, language, traditions, and life because of colonization and the settlers who have come since have benefited from that loss tremendously. And through this loss, settlers have also missed out on learning from this traditional knowledge and applying it to our relationships with the land and with each other. Remember, Indigenous Peoples are still here and not all opportunities to learn from these teachings has been lost as long as settler society is willing to listen and adapt.

On this 152nd anniversary of the Constitution Act, I will be taking time to reflect on what legislation has led us to today and what acts of defiance will help us heal from it. The story we tell ourselves about who we are as Canadians is based in this idea of a cultural mosaic – a place where you can come to practice your culture, speak your language, and teach your traditions to your children. But it is those very things that were taken away from the Indigenous People who were here first. Let’s start telling the truth and reconciling its impact, in our publicly funded institutions and in ourselves.

Happy Decolonization Day, everyone!

Thank you for sharing this Miranda. I was present before the museum was opened to partake in a transfer ceremony for a pipe that belongs to a Stoney nakota family from Alexis Nakota Sioux nation. The pipe was being moved from the old museum location to the new location and a family member came to pray for the pipe and it’s travels to its new home . The pipe wasn’t lent to the museum by itself, it had a pipe bag, a wire pipe cleaner and a piece of a sweet grass braid. Upon arrival to do the ceremony, it was quickly notice that the pipe would be the only object that would be travelling to the new museum space. I quickly commented that all objects with the pipe needed to travel together as they contain the same story, spirit and energy. Museum staff said that it was not possible and the pipe would be just travelling by itself as it would be the only object appearing in the display. The family member that was performing the prayers and ceremony, didn’t say much and knew just to pray over the pipe as it was as it wasn’t the time or place to argue about it . This was just one example and I really wonder how many other important family items have been separated or even misplaced throughout many institutional system rules . I believe the family has begun an administrative process to take the pipe back to the family but from what I heard, it will be several years processing, as you stated above, the rules are only changing within Blackfoot negotiations.

Also, the family member asked about lending an 100 year old men’s chicken dance outfit for display in the museum and he was told that if he lent it that it would be for ever and there would be no opportunity to get it back.

Thank you again Miranda for sharing your thoughts honestly and openly, The treatment of artefacts and information from first nation communities and families isn’t well known to our government systems and employees nor the differences between language groups, teachings and ceremonies.

Thank you, Michel, for sharing this personal story and for taking the time to read. I believe we all have a responsibility to call-out colonial systems that are imbalanced and unfair then advocate for change.

Thank you for this thoughtful, open, and brave post Miranda. You’ve given me a lot to think about for when I (finally) go see the new RAM. Thank you also, Michael, for sharing your story – really disappointing to hear.

Thanks for reading. If you’d like to plan a trip to the museum together, let me know!

Thank you for supporting the article.

Yes and we got the most amazing human rights lawyer to boot.

There’s a time and place when this shit needs to stop and we are supporting her 100 %, no more from them now and in the future!!!

They are government of Alberta employee plus the Alberta Provincial Employee Union is amazing! and its so unbecoming for them to treat our ancestors and artifacts/ culture like that this generation needs to fight hard and take their place in society cause they are equivalent in education, skills and they have the culture roots and backbone to fight for the rights of us the Cree and other communities and they inherited guidence by our Star people and their Grandparents. No backing down. I’m so proud!!

Oh we took that pic when were we picking sage by Battle River 2 summers ago, it was so beautiful, by 5 mile straight down in Samson territory, how beautiful this picture rep. Treaty Six, Samson Cree Nation, our Home and traditions learned from our Nohkom Sarah Swampy, Our Aunties and My Nimana Grace!

Place your tobacco down. That day we prayed as women to call on our Ancestors to guide the move of the stone, ever so careful (just crying now) the prayers meant so much to me as her mom to guide her with moving the Manitou Stone..on that short but powerful journey to its rightful home for display…and all that sage we exchange for the tobacco currently sits under the stone at RAM. We took care of our part in ceremony the GOA staff should also grrrrr

They will never understand why we do things in ceremony for the unborn grandchildren, who are from our first nations communities! We are our ancestors reborn and our legacy to carry on our prayers, ceremony and our roots to the community!

https://www.thestar.com/news/canada/2020/06/27/im-not-your-token-indigenous-employee-accuses-alberta-museum-of-systemic-racism.html?fbclid=IwAR0KVdOVxvlI6uPDWsviompeGfxTyEx9-lDBKelXUnSXq_wtKJlWXmKEOs0

Hi Miranda! I attended a field trip with my Indigenous Studies class you lead a year ago with the school Harry Ainlay, and I wanted to thank you for opening my eyes to all of the little things I never would have recognized or noticed about the museum. For example, the unwelcoming east side of the building compared to the welcoming west side that is pointed towards the courts, city centre, art gallery etc. Or certain exhibits that could be redone, like the residential school closed off circle, which I probably never would have walked into. There were also so many more things that blew my mind, and it’s crazy to think about how subtle all of them were. Which is why I believe it’s so important to share your opinions and put your voice out into the world, because if I, and Indigenous girl, didn’t notice any of these little injustices then non-Indigenous people won’t. I learned a lot that day, and I want to thank you.